Open source matters in hardware, too – Interview

(Article originally published on Ars Technica)

Jon Brodkin of Ars Technica conducts a Q&A with Massimo Banzi as Arduino’s rise continues.

Most of the technology world is familiar with open source software and the reasons why, in some eyes, it’s more appealing than proprietary software. When software’s source code is available for anyone to inspect, it can be examined for security flaws, altered to suit user wishes, or used as the basis for a new product.

Less well-known is the concept behind open source hardware, such as Arduino. Massimo Banzi, co-creator of Arduino, spoke with Ars this month about the importance of open hardware and a variety of other topics related to Arduino. As an “open source electronic prototyping platform,” Arduino releases all of its hardware design files under a Creative Commons license, and the software needed to run Arduino systems is released under an open source software license. That includes an Arduino development environment that helps users create robots or any other sort of electronics project they can dream up.

So just like with open source software, people can and do make derivatives of Arduino boards or entirely new products powered by Arduino technology.

Why is openness important in hardware? “Because open hardware platforms become the platform where people start to develop their own products,” Banzi told Ars. “For us, it’s important that people can prototype on the BeagleBone [a similar product] or the Arduino, and if they decide to make a product out of it, they can go and buy the processors and use our design as a starting point and make their own product out of it.”

While Arduino has been around since 2005, the Raspberry Pi has been the hot platform for hobbyists over the past 18 months. But the Pi’s hardware isn’t open.

“With the Raspberry Pi you cannot even buy the processor,” Banzi said. “With the processor on the BeagleBone, you can go buy even one of them if you need to.” Raspberry Pi is “a PC designed for people to learn how to program. But we are a completely different philosophy. We believe in a full platform, so when we produce a piece of hardware, we also produce documentation and a development environment that fits all together with hardware.”

BeagleBone and Arduino, partners in open hardware

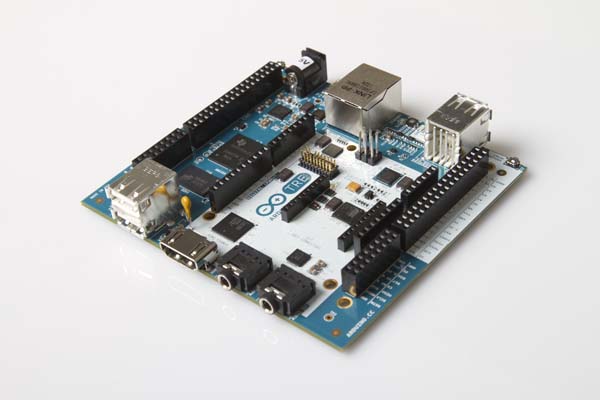

You may have noticed that Banzi spoke positively about the BeagleBone even though it’s ostensibly an Arduino competitor, made by the BeagleBoard.org foundation and CircuitCo. The platforms share the same open hardware philosophy, and they recently collaborated to build the Arduino Tre, scheduled to be released in spring 2014.

The Arduino Tre and BeagleBone Black both use a 1GHz Sitara AM335x ARM Cortex-A8 processor from Texas Instruments. BeagleBoard.org co-founders Gerald Coley and Jason Kridner helped the Arduino team design the hardware and software for the Tre, according to Senior Embedded Systems Engineer David Anders of CircuitCo. Like the BeagleBone, the Tre is manufactured by CircuitCo.

The collaboration “began as a discussion about how to introduce users (not just students, but also artists, designers, sociologists, and anyone who doesn’t come from a CS/EE background) to what embedded Linux offers without assuming that they know Linux,” Anders told Ars.

Software will also be portable between the two platforms. “The Arduino Tre does contain the essential core of a BeagleBone Black, and we are working to standardize the default distribution between the two platforms, which would provide easy transition between working on either platform,” Anders said.

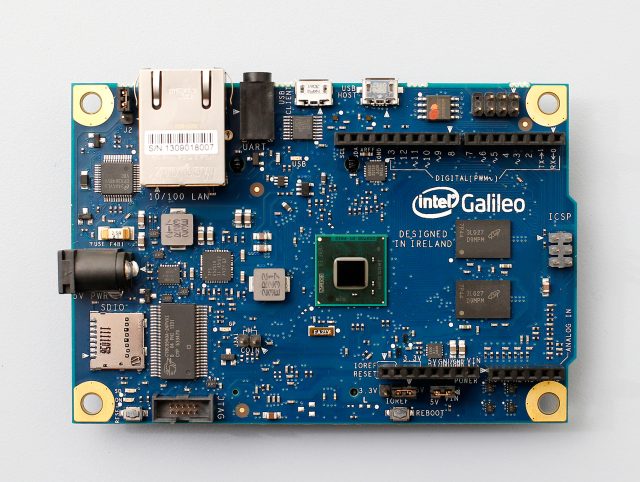

In another development important for open source hardware, the creators of BeagleBoard andArduino have each developed platforms containing Intel processors for the first time.

At the LinuxCon conference, Intel CTO Dirk Hohndel told the crowd that CircuitCo’s Minnowboard is “specifically designed as the first open hardware board based on x86, and that allows you to build derivatives without an NDA. All the pieces are open and available, all the blueprints you need, all the source files you need. You can create your own embedded platforms without Intel, without any of the vendors involved.”

After the Minnowboard’s release, Intel teamed with Arduino to create the Intel Galileo, due out next month for $60 or less.

Intel’s embrace of open hardware came in response to customer demand. Banzi heard one story about Intel unsuccessfully trying to sell a customer a new processor. “The customer told them, ‘I’m not moving even if you give me the processor for free because I don’t want to lose the community,'” Banzi said. “For this person, it was very important to have a platform based on Arduino and the Arduino community behind it.”

An Arduino for every project

Banzi co-developed Arduino while teaching at a design school in northwest Italy, simply because there weren’t any good hardware options for his students. “We had to figure out something that would be simple, cheaper, USB plug and play, and you could program on Windows, Mac, and Linux,” he said.

“Arduino allows you to move your code across platforms so you can always choose the platform that fits with your project.”

Arduino was expected to be useful “in that particular tiny context,” but it morphed into something much bigger. “It sort of escaped the lab—let’s put it this way, you know like a virus—and started to touch all sorts of different other markets,” Banzi said. “Now if you go to the Maker Faire, you see that 80 percent of the projects are running on Arduino in one way or another.”

There are about a million official Arduino boards “out in the wild” and perhaps several million more of the unofficial variety, he said. Arduino is trademarked—even though it’s open hardware, makers of new products should “explicitly say that you’re not connected to Arduino and your product is a derivative,” the company says.

While some Arduino clones are made well and are compatible with Arduino software, there are many cheap knockoffs, Banzi said. “There is a problem that a number of people have started to use the ‘Arduino compatible’ words too much,” he said. “There’s no guarantee it’s going to be compatible or that you can use the official Arduino IDE [integrated development environment] to program it.”

A company called Seeed Studio has done a good job making products that are compatible and respectful of trademarks. But there are many bad apples, which Banzi has catalogued on his website.

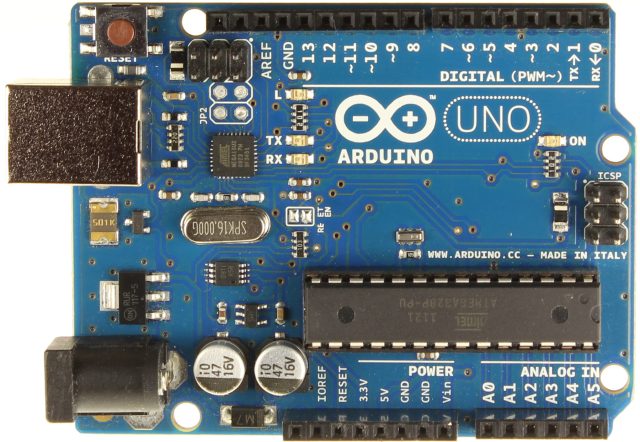

Beyond that problem, pretty much everything is going great for Arduino. The new Intel- and ARM-based Arduinos take their place alongside existing boards like the Arduino Uno, based on the ATmega328 8-bit microcontroller.

“The Arduino Uno is the cornerstone of Arduino, that’s where everybody starts,” Banzi said. “You learn how to fly with the Arduino Uno and then you graduate to different boards.”

The Arduino partnership with Intel is going to yield more fruit, as the Intel Quark processor is designed in such a way that new versions with slightly different capabilities can be rolled out quickly, Banzi said. “We have a collaboration agreement where this is just the start.”

The Intel Galileo runs a stripped-down, custom version of Linux and is ideal for building 3D printers or applications that are part of the “Internet of things.” That includes home automation applications and wireless sensor networks.

It’s not clear whether the Intel Galileo or the Arduino Tre is more powerful, as Banzi said no benchmarks have been run to compare them. They have different capabilities and tradeoffs, though. The Tre can run a desktop and is thus suitable for applications where you need time-sensitive I/O operations and a graphical interface, such as Kinect-like sensors.

The Galileo opens Arduino up to the world of x86 applications, but it lacks a video card and is imagined as a platform for applications that don’t need a desktop interface, Banzi said.

Previous-generation Arduinos are not obsolete, either. Last year’s Arduino Due, for example, uses a 32-bit processor which is “good for those applications where timing is important,” like a 3D printer or stepper motor, Banzi said. “8-bit processors are starting to struggle on the more interesting printers.”

What’s significant is that Arduino has a piece of hardware for almost every use case.

“We are moving to a situation where you would be able to scale your code from an 8-bit microcontroller to a 32-bit microcontroller, to a 400MHz Intel chip, all the way up to a 1GHz ARMv7 computer with HDMI,” Banzi said. “Arduino allows you to move your code across platforms so you can always choose the platform that fits with your project.”